By Bryan Baker

To the untrained eye and incurious, the California desert may seem a barren wasteland. When I was a kid, my family would drive across the desert toward points east or north, and I’d be bored through the hours it took to get through the seemingly endless miles of creosote and other desert bush. Nowadays it seems a lot of people are ready to dismiss the desert as only good for something like cattle grazing, or at best, vast stretches of solar panels or windmills.

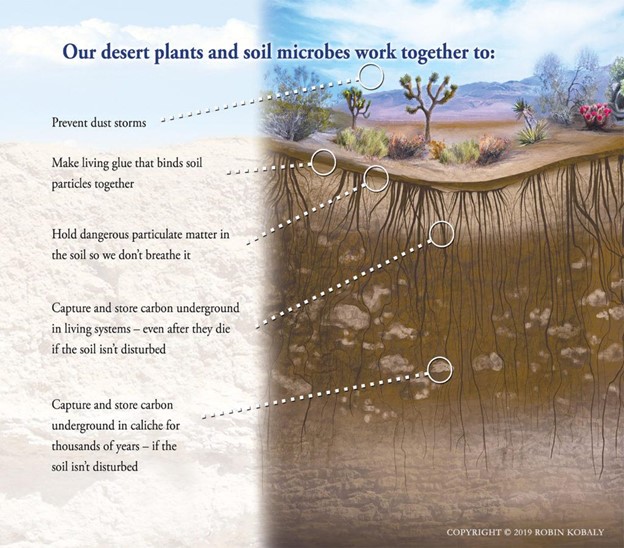

However, if you take the time to look, you will find an ecological wonderland both above and below ground. The California desert is teeming with complex systems that allow for a trifecta of life to flourish: flora, fauna, and people. It is home to 38% of our native plant species, a large diversity of bird and animal life, varied climates, and unique topography and geology. Across the California desert, there are over 100 major mountain ranges, canyons, playas, alkali meadows, badlands, and ancient aquifers.

Despite the scores of scientific studies and research that prove the importance of the desert ecosystem to our health and to regional environmental balance, one Los Angeles-based corporation is willing to dismiss these important contributions to profit from an unsustainable approach to extracting ancient water from a desert aquifer.

For over two decades, the Cadiz Corporation has sought to pump groundwater unsustainably from an aquifer in the California desert and export it via pipeline to other parts of California for profit. Cadiz would “mine” precious groundwater by annually pumping 2 to 5 times more water from the aquifer than is recharged by rain or snow, according to a US Geological Survey study. The aquifer cannot be recharged by precipitation as quickly as it would be depleted, making this a short-term, unsustainable solution at best. This significant overdraft would only increase in severity due to climate change, which has been making the Mojave Desert hotter and drier.

Cadiz claims they would pump water that would otherwise evaporate away. But their claims have not stood up to independent scientific review. A study in a scientific journal (Environmental Forensics, April 2018) that was reviewed by independent scientists found that the aquifer that Cadiz wants to mine is linked to other springs in the eastern Mojave Desert, and could cause irreparable damage to the ecosystems in those areas. One of these—Bonanza Spring—is the largest water source in a thousand square miles. In a warming, drying desert, such water sources are crucial to the survival of desert wildlife such as bighorn sheep, as well as migrating birds on the Pacific Flyway.

This would also have disastrous impacts on cultural resources and cultural landscapes sacred to Tribal Nations, such as Fort Mojave and the Chemehuevi, local communities, desert wildlife, and nearby protected lands like Mojave Trails National Monument.

The Cadiz project is opposed by the National Congress of American Indians (resolution), the Tribal Alliance of Sovereign Indian Nations which is made up of nine of the largest federally recognized tribal governments in Southern California (letter and Op-ed), the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe (statement), the Twenty-nine Palms Band of Mission Indians (statement), and the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe (resolution).

Indigenous peoples in the desert have relied on springs for their very survival since time immemorial, and still hold these springs as culturally important. They have proclaimed that losing those springs would mean eroding the intact cultures of desert Native peoples. In stating its opposition to Cadiz, the Chemehuevi wrote: “Our Tribe knows that the Cadiz Project is not a conservation project and its aggressive pumping of water fails to save water for our children, grandchildren up to the Seventh Generation.” The Fort Mojave Indian Tribe noted: “The scope and scale of the Cadiz Project would be hugely detrimental to the Traditional Lands of the Fort Mojave.”

A Branding Reinvention Exposed

In the face of overwhelming anti-extraction sentiment, you would think the Cadiz efforts would cease. Rather than concede their pursuit of a bad idea, the Cadiz Corporation is trying to justify their extractive actions through a rebranding. They now want us to believe that they are a movement for Human Rights to Water, in pursuit of bettering the lives of Californians in frontline communities, because a portion of their exported water would go to disadvantaged communities. But how true is this and at what cost?

The water mined by Cadiz is not clean but contains hexavalent chromium at concentrations up to 16 parts per billion as well as high levels of arsenic, a known and already regulated carcinogen. The state is now considering a drinking water standard of 10 parts per billion for hexavalent chromium and health advocates are asking for an even lower standard. Already, the cost to provide safe drinking water has left hundreds of community water systems in the state unable to provide safe and affordable drinking water for their customers and has created a $10 billion backlog in safe drinking water projects. The unreliable, unsustainable Cadiz project would only add to the already heavy cost of meeting the Human Right to Water and would be a waste of time and energy that should be focused on real solutions, not empty rhetoric.

The water provided by Cadiz is not affordable. The cost of pumping and delivering this water, added to the cost of water treatment, would make this water more expensive than most current water sources. Nearly a third of all California households already struggle to pay water bills that are increasing faster than the rate of inflation. This project only makes that problem worse.

Frontline communities need a voice in discussions of where their water will come from. One of the most important ways members of frontline communities can speak their minds on such projects is by weighing in during environmental analysis of those projects under the review processes, known as NEPA (federal) and CEQA (state). Cadiz has long sought to evade federal environmental analysis for its project. Recently, Cadiz funded an organization called Groundswell, which drafted state legislation that would exempt Cadiz and most water projects from such scrutiny. This would deprive frontline communities of one of their most important public participation tools. Is it serving those communities’ interests to force them to drink expensive, contaminated water while refusing to allow those communities a voice in the decision?

The Greater Los Angeles area, desert communities, disadvantaged communities, our overall health, tribal nations, and the ecological flora and fauna deserve better. Consider educating others about Cadiz’s ongoing attacks on our health and sign up to receive action alerts that will keep you updated if and when Cadiz continues its course to deplete the desert. Your lungs, our desert communities and future generations will thank you.

Bryan is the Mojave Group chair for the SC San Gorgonio Chapter.