The River Project’s website

http://www.theriverproject.org/index.php Home Page

If you were a Chumash Native American living 300 years ago or even a resident living in Los Angeles in the early 1900s you would have witnessed a lovely rambling L.A. River that would regularly flood its banks. All that changed in the 1930s when there was an extremely damaging flood and that is when the government decided to make a concrete floor and sides to the river so it could not wander or flood anymore. That fix did tame the river but there was a price to pay for the luxury. According to The River Project, it was estimated by L.A. County Flood Control engineers that before the river was concretized about 80% of the L.A. River water that came down from the mountains was absorbed into the San Fernando Valley’s (SF Valley) gigantic aquifer basin. Now because the SF Valley is so extensively paved over & the L.A. River is contained in concrete, we only retain about 8% of the water. Rain water is funneled from non-porous streets right into the L.A. River and out into the ocean. There is not enough time or the right conditions for the water to sink into the ground. That 8% water retention is not enough for our huge population so we have to import water from northern California and, also, from the Colorado River. That is problematic because those places are not giving us the allotment they did even 10 years ago and that means we need to rely more on our local water. We currently spend $1 billion a year to import 85 percent of our water supply from other regions whose ecosystems are seriously threatened by that loss.

Where our used water ends up.

If you were to put a drop of vegetable oil down your sink drain or put some paper in the toilet and then you used water to flush them away, they would both go down our extensive waste pipe system and travel to our Tillman Waste Water Treatment Plant in the Sepulveda Basin of the SF Valley. The water & oil parts would be treated at the Tillman plant and the water would be sent through a series of decorative ponds in the Japanese Garden that is next to the Tillman Plant. They would go to the Sepulveda Wildlife Lake & Balboa Lake and then to the L.A. River and out to the sea in a relatively clean condition. The paper would be sent to the Hyperion Waste Treatment Plant on the coast where it would be treated with heat & other processes to sterilize it and then taken to be used as fertilizer. If you were to drop the same oil and paper on our streets just before a rain, they would be swept untreated down our storm drains to the L.A. river and out to the ocean where they can affect both the water quality of the ocean and our marine life. This is especially true if the object was plastic instead of paper.

About Our 4 City of Los Angeles Watersheds

A watershed is an area or region of land whose runoff drains into a creek, river or other body of water. Since much of Los Angeles is paved, many people are not aware that we have watersheds here in Southern California. However, the truth of the matter is that we all live in a watershed. Los Angeles has four primary watersheds and they are:

Los Angeles River Watershed, which is by far the biggest

Ballona Creek Watershed

Santa Monica Bay North & South Watershed

Dominguez Hills Channel Watershed

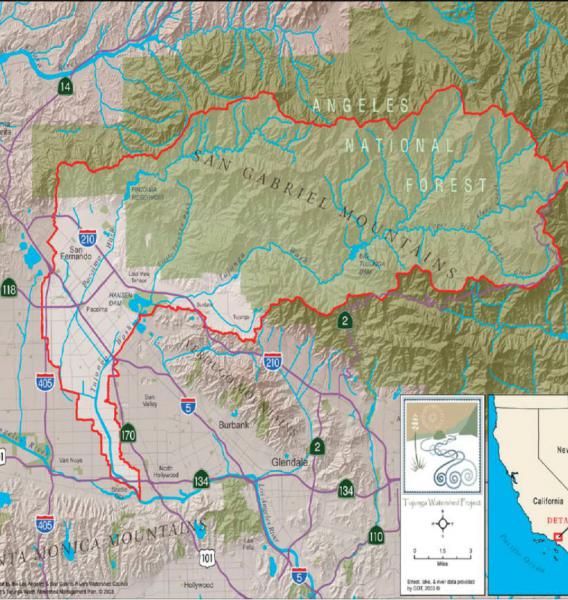

TO GET AN IDEA OF THE SIZE OF THE 4 PRIMARY WATERSHEDS, SEE THE GRAPHIC MAP BELOW:

The San Fernando Valley’s watershed is the Los Angeles River Watershed and it is in orange. The dark orange is in the city and the lighter orange is the more rural and less polluted areas outside the urban area. Our L.A. River Watershed is the largest one and within this sizeable L.A. River watershed is a 225 sq. mile sub-watershed named the Tujunga/Pacoima watershed: most of it is located in the SF Valley. The Tujunga/Pacoima Sub-watershed is the biggest one within the L.A. River watershed. Notice most of the reservoirs are in the San Fernando Valley and SF Valley plays a significant part in supplying Los Angeles with local water through the reservoirs and ground water basins. See the L.A. Storm Water website for more information.

Why our Tujunga/Pacoima watershed is important to Los Angeles.

This figure below shows the red outline of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed.

Map and information provided by The River Project (TRP)

A watershed is an area or region of land whose runoff drains into a creek, river or other body of water. Since much of Los Angeles is paved, many people are not aware that we have watersheds here in Southern California. However, the truth of the matter is that we all live in a watershed. Los Angeles has four primary watersheds, and they include:

(1)Los Angeles River Watershed, which is by far the biggest, (2) Ballona Creek Watershed, (3) Santa Monica Bay North & South watershed (4) Dominguez Hills Channel watershed

The figure above shows the extent of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed, which is the area in-between the red lines. The water that falls on this area flows into the San Fernando Valley. It is important to pay attention to the quantity & quality of water that enters the SF Valley if we want to reduce the amount of water we import, as was discussed above. The Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed is the largest subwatershed of the Los Angeles River Watershed and encompasses 225 square miles in north-central Los Angeles County, California. It includes both remote open space of the Angeles National Forest and the urbanized lands of the cities of Los Angeles and San Fernando, at elevations that range from about 560 to 7,130 feet. You can see the San Gabriel, Verdugo & Santa Monica Mountains in the map above.

This is the Big Tujunga Reservoir & Dam. This Reservoir is an important part of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed.

(see red reservoir on map below or the blue lake in the San Gabriel Mountains in map above))

As part of the project to supply more local water, Big Tujunga Dam will be structurally rehabilitated to provide significantly enhanced storage capacity, improved downstream flood protection and a modified flow release regime designed to support more wildlife. They would dredge behind the dam so it will hold more water.

(Photo by NPS for River Project)

Support habitat viability for the Great Egret. Because the Valley has become so urbanized it has destroyed habitat and the wildlife that depend on these wild places.

Support habitat viability for the Great Egret. Because the Valley has become so urbanized it has destroyed habitat and the wildlife that depend on these wild places.

(NPS photo for the River Project)

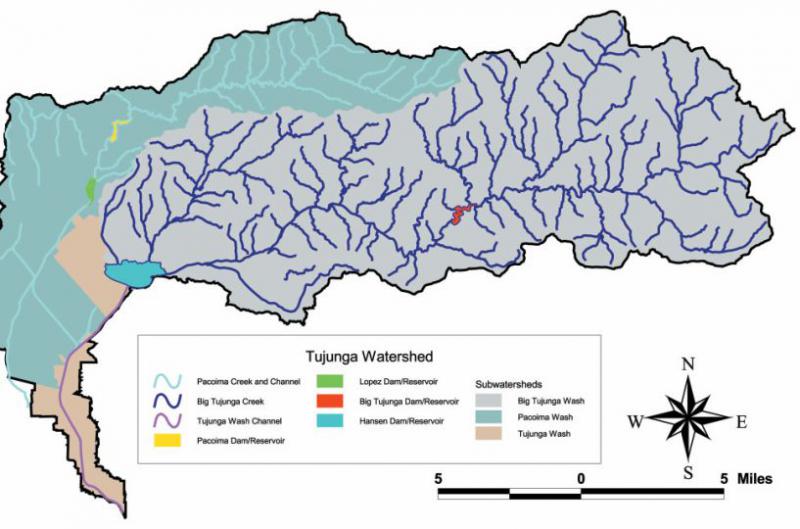

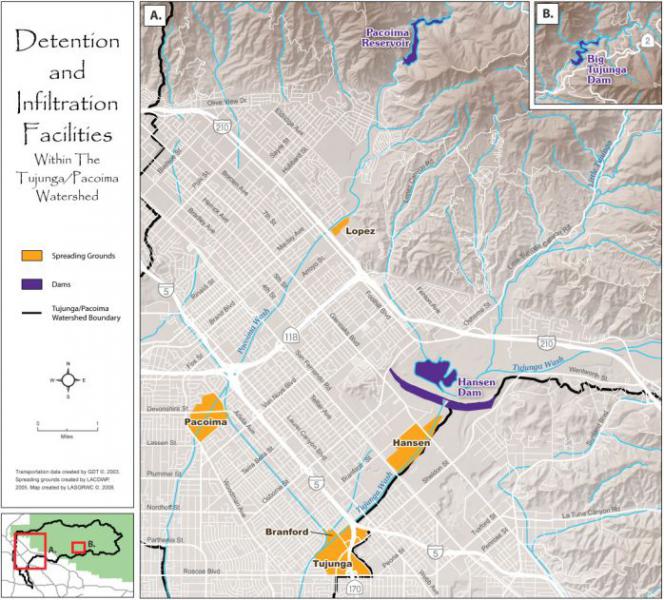

Map provided by “The River Project”

When it rains & snows, more water is generated in the mountains than in the flat San Fernando Valley (SF Valley). The rain that falls in the SF Valley is generally from 11 inches to 15 inches per year but in the mountains above, the averages is from 20 to 35 inches per year. In the SF Valley, this water comes rushing down the mountains and over asphalt & concrete in the Valley to the storm drains, then it quickly flows into the concrete channelized Tujunga and Pacoima washes and out to the LA River. Before we can catch the majority of the water it arrives into the ocean so very little of it seeps into the ground to become ground water. Many citizens and officials want to change this situation so that we can rely on more of our ground water and less imported water.

When the rain & some snow flows down from the mountains some of it is stored in reservoirs. In our area we have 4 of them and you can see them in various colors in the figure above. The largest subwatershed is the Big Tujunga sub watershed, in gray, the Tujunga (in red) & Hansen (in blue) Reservoirs are used to catch that water. The turquois area is the Pacoima subwatershed and the 2 reservoirs used to catch its water are Pacoima Reservoir, in yellow, and the Lopez Reservoir, in green. There are times when the reservoirs are not big enough to catch all the water and then the surplus must be released into the Pacoima & Tujunga concrete channelized rivers on its way to the LA River and out to the sea. The watershed can generally be described in two parts: the upper watershed (above Hansen and Pacoima Dams), which is relatively undisturbed open space, and the lower watershed, which is mostly urbanized and highly degraded. Approximately 80 percent of the land within the overall Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed is undeveloped. The vast majority of it is in the federally protected Angeles National Forest of the upper watershed. As you can see from the above figure, dozens of streams feed the three main tributaries—the Big Tujunga, Little Tujunga, and Pacoima Washes. Pacoima Wash becomes channelized below the Lopez Debris Basin. Big and Little Tujunga Wash meet in the reservoir behind Hansen Dam. Below Hansen Dam, Pacoima Wash joins the channelized Tujunga Wash as it flows to its confluence with the Los Angeles River in Studio City. The Big Tujunga Wash is the largest, making up 68% of the watershed, followed by Pacoima Wash (27 percent) and Tujunga Wash (5 percent). Four dam/reservoirs—Big Tujunga, Hansen, Pacoima, and Lopez—control mountain runoff and limit natural sediment transport.

Pacoima Reservoir is used to catch water flowing down the mountains. This Reservoir is part of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed. There are plans to dredge the lake to make it deeper to hold more water.

Pacoima Reservoir is used to catch water flowing down the mountains. This Reservoir is part of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed. There are plans to dredge the lake to make it deeper to hold more water.

(Photo NPS for The River Project)

The San Fernando Groundwater Basin (SFB)

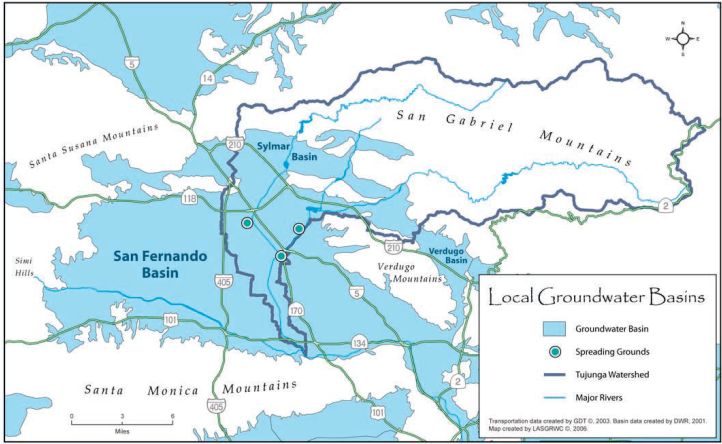

(San Fernando Basin Map provided by The River Project)

San Fernando Basin (SF Basin)

(LADWP is LA Dept. of Water & Power) (TRP is The River Project)

(TRP) “In a reasonably healthy condition, the primary function of the watershed would be to infiltrate, filter and store local rainfall within its large underground reservoir: the San Fernando Groundwater Basin. The groundwater basins in the watershed are critical to local water supply. The capture, storage, and infiltration of snowmelt and stormwater in these basins have the potential to significantly increase the amount and reliability of local supplies.” (LADWP) “The SF Basin encompasses an area of approximately 175 square miles and it is about 1,200 feet deep. The area of the SF Basin roughly to the west of the San Diego Freeway has a low permeability (absorption) whereas the area roughly to the east of the San Diego Freeway has a high permeability. The depth of water in the area with high permeability, which contains the majority of the City of Los Angeles’ groundwater production wells, is between 30 to 375 feet below the ground surface elevation. Due to the San Fernando Valley topography and geology, the groundwater in the SF Basin primarily moves in a southeasterly direction towards the intersection of the Golden State and Glendale Freeways. The SF Basin and its watershed is a tributary to the Los Angeles River. The underground water eventually surfaces in the vicinity of the Los Angeles River and Glendale Freeway and flows out to the Pacific Ocean.”

Groundwater Supplies in the San Fernando Basin (SF Basin)

We have a huge ground water storage capacity in the San Fernando Valley. The blue areas in the map above show the places that are capable of storing water. To get the water from the reservoirs above into the ground water basins, spreading grounds are used and they are represented by the circles in green on the map. Per the LADWP 2010, “The local groundwater has historically provided approximately 11 to 15 percent of the city’s total water supply. During times of drought and/or emergencies, the local groundwater has provided up to 30 percent of the total water supply.”

(LADWP) The effective utilization and protection of our local groundwater is a key component of the City of Los Angeles’ Water Supply Action Plan. The SF Basin plays a very critical part in securing the future of our water supply. This is because the SF Basin groundwater accounts for more than 80% or 87,000 acre-feet per year (AFY) of the City of Los Angeles’ total local groundwater entitlements. The City of Los Angeles also has groundwater rights in Eagle Rock (500 AFY), Central (15,000 AFY), West Coast (1,503 AFY) and Sylmar (3,405 AFY) Basins. As per the River Project, “The City of Los Angeles owns water rights in two Upper Los Angeles River Area groundwater basins in the Tujunga Watershed: the San Fernando (under the lower watershed) and the Sylmar (in the area along the Pacoima Wash above Lopez Dam) with a combined capacity of 3,510,000 acre-feet. This water from the SF Basin is used as potable water after treatment to meet applicable drinking water standards. However, groundwater levels in these basins are well below capacity.”

Chart shows how residential & business runoff can affect our water supply.

Chart from The River Project

Geology of Pollution in San Fernando Valley

Geology of Pollution in San Fernando Valley

(LADWP) “An unconfined aquifer, the San Fernando Basin (SF Basin) has no defined or continuous layers of clay and/or silt (aquitards) to separate the groundwater into different zones. Simply put, the San Fernando Basin is like a very large bathtub filled primarily with sands and gravels with some silts and clay. The voids in the sands and gravels are filled with water. Since the SF Basin is an unconfined aquifer, any surface contamination and/or improper disposal of hazardous constituents will eventually work its way down to the groundwater and depending upon their solubility properties, their plume could very quickly spread throughout the entire basin. In confined basins elsewhere with distinct zones such as shallow and deep zones, the groundwater contamination is generally limited to the shallow zone of the aquifer unfortunately this is not the case in the SF Basin. As of May 2010, LADWP has removed from service 54 of its 115 groundwater production wells in the SF Basin due to groundwater contamination.” Per TRP, pockets of contamination are located largely outside the watershed boundary, but increases in groundwater levels overall could affect water quality throughout the aquifer.

San Fernando Valley Pollution History

(LADWP) “Over the past 70 years, the San Fernando Basin (SF Basin) groundwater has been contaminated by a variety of sources. Aircraft manufacturing operations dating back to World War II through the Cold War, accounts for the majority of the groundwater contamination in the SF Basin. Other manufacturing activities, automobile and equipment repair, automobile recycling, unlined landfills, dry cleaners, paint shops, chrome plating, textile manufacturing, fuel storage and dispensing, chemical manufacturing, past dairies, agricultural and residential use of chemical fertilizer and septic systems have also contributed to the contamination of groundwater in the SF Basin. Prior to environmental regulations instituted in the 1970s requiring regular inspections by local and/or State agencies, many chemical users had leaky underground storage tanks, internal piping and disposal was often via pits dug into the ground, which allowed chemicals to percolate into the soil and make their way into the groundwater. In 1986, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) designated the easterly portion of the San Fernando Basin and parts of cities of Burbank and Glendale as Superfund Sites due to the groundwater contamination.”

Per the EPA: “San Fernando Valley (Area 1) is an area of contaminated groundwater covering approximately 4 square miles beneath the North Hollywood section of the City of Los Angeles and the City of Burbank. This area is part of the San Fernando Valley Groundwater basin, an aquifer which provides drinking water to over 800,000 residents of the Cities of Los Angeles, Burbank, and Glendale, and the La Crescenta Water District. Approximately 3 million people reside within three miles of this site. In 1980, concentrations of chlorinated volatile organic compounds (VOC), including trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE), were found to be above Federal Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and State Action Levels in many city production wells. Those solvents were widely used in a number of industries including aerospace and defense manufacturing, machinery degreasing, dry cleaning, and metal plating. Some contaminants currently affecting the basin’s water supply can be traced as far back as the 1940s, when chemical wastes disposal was unregulated throughout the Valley. In response to the public health threat, the cities were forced either to shut down their wells and provide alternate sources of drinking water or blend contaminated well water with water from clean sources. Results of a groundwater monitoring program conducted from 1981 to 1987 revealed over 50 percent of the water supply wells in the eastern portion of the San Fernando Valley Groundwater Basin were contaminated. More than 60 public drinking water supply wells are located within the Area 1 site perimeter; 56 are owned and operated by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, and 11 are owned and operated by the Burbank Public Service Department. The shutdown of many of these wells has resulted in the cities turning to more expensive sources of drinking water, and has limited use of a substantial drinking water supply in an area where this resource is already scarce.”

As you can see, there is a dilemma regarding the storage of water underground. Do we take advantage of all this free storage space but maybe risk storing the water in a less than clean place? We might not have any choice if portions of the imported water are withdrawn from us.

Picture of a groundwater testing well from the River Project site

LADWP’s Future Groundwater Plans

LADWP has been working with State and Federal regulatory agencies including, but not limited to, the USEPA, State Water Resources Control Board, Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board, California Department of Toxic Substances Control, and California Department of Public Health to develop solutions for cleanup of the San Fernando Basin (SF Basin) groundwater. Other steps LADWP has taken to address the groundwater contamination and protect the city’s drinking water supply include:

- Developing historical water quality information;

- Developing TCE and PCE contamination data;

- Conducting a soil gas survey;

- Installing 87 shallow and deep groundwater monitoring wells;

- Closely monitoring groundwater elevation and water quality from groundwater monitoring and production wells

- Constructing the North Hollywood Operable Unit to extract and cleanup groundwater in the North Hollywood Area

- Constructing the Pollock Groundwater Treatment Plant to extract and cleanup at the most southerly end of the SFB;

- Constructing Tujunga Wellfield Liquid Phase Granular Activated Carbon Pilot Treatment Plant to cleanup groundwater in the Tujunga Area; and,

- Increasing water quality monitoring and testing.

LADWP currently conducts nearly 250,000 field and laboratory tests on more than 25,000 samples collected throughout the year for hundreds of different chemicals to ensure the safety of the City of Los Angeles’ drinking water.

Moving forward, LADWP is planning to install up to 40 additional groundwater monitoring wells in the SF Basin and is developing short- and long-term solutions to restoring the City’s ability to fully utilize its rights to water in the SF Basin. One short-term solution currently under consideration is the construction of additional pilot treatment plants to evaluate new and promising treatment technologies. LADWP is also working with the USEPA on upgrading the existing North Hollywood Operable Unit to cleanup and treat additional groundwater contaminants from the North Hollywood Area.

As a long-term solution to cleanup and treatment of contaminated groundwater in the SF Basin, LADWP is in the early stages of developing a groundwater treatment complex, utilizing the best available technologies. LADWP is anticipating constructing such a treatment complex by as early as 2018, subject to securing all necessary permits and approvals.

L.A. Times article 6-23-13: “DWP to build groundwater treatment plants on Superfund site.”

Per the L.A. Times, “The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power plans to build the world’s largest groundwater treatment center over one of the largest Superfund pollution sites in the United States: the San Fernando Basin. Two plants costing a combined $600 million to $800 million will restore groundwater pumping of drinking water from scores of San Fernando Valley wells that the DWP began closing in the 1980s, the utility said. The plants also will ensure that other wells remain open despite pollution plumes steadily migrating in their direction. One treatment center will be built on DWP property in North Hollywood just north of Vanowen Street, between Morella and Hinds avenues. It will process three times as much water per second as the world’s largest existing groundwater treatment facility, officials said. The DWP will build a second, slightly smaller center near the intersection of the 5 and 170 Freeways.”

“At the current rate of migration of pollutants, the city would be unable to use most of its groundwater entitlements in the basin within five to seven years, forcing it to buy and import more expensive water from the Metropolitan Water District, DWP officials said. Construction is to begin in five years, said Marty Adams, director of water operations for the DWP. The DWP hopes to have both centers operating by 2022, producing about a quarter of the 215 billion gallons the city consumes each year.”

“The DWP is currently drilling monitoring wells throughout the region to identify as many contaminants as possible and develop strategies for removing them, said Susan Rowghani, director of DWP’s water engineering and technical services. Each contaminant will require its own specialized purification process. For example, the current process for removing TCE is to pump water to the top of an aeration tower and, as the water flows back down, use an upward blower to send a countercurrent through it. TCE becomes trapped and is vaporized into a controlled airstream that is then filtered through activated carbon to ensure that it is not released into the atmosphere.”

Health Issues caused by these contaminants:

The San Fernando Basin accounts for more than 80% of the city’s total local water rights, but because of contamination plumes of toxic chemicals including hexavalent chromium, perchlorate, nitrates and the carcinogen trichloroethylene (TCE) only about half of its 115 groundwater production wells are usable. The EPA determined in 2011 that TCE can cause kidney and liver cancer, lymphoma and other health problems. The public can be exposed to TCE in several ways, including by showering in contaminated water and by breathing air in homes where TCE vapors have intruded from the soil. TCE’s movement from contaminated groundwater and soil into the indoor air of overlying buildings is a major concern.

Info from L.A. Times article 6-23-13: “DWP to build groundwater treatment plants on Superfund site.”

To save water plant drought tolerant trees, such as these oaks.

(Picture by Sierra Club member Gayle Dufour)

Why we need to develop our local water and our ground water basin.

Because of climate change there is a good chance that we will have substantially less water supplies in California and in the western part of the USA. This means that there will be less water to import to Southern California and the imports could get more expensive. If we don’t want to be hit with huge decreases in water that are available to us, we have to plan ahead and use the resources that we have been given, such as catching the water that does come to us in the form of rain & snow. The River Project’s report says, “Global climate changes in the twenty-first century are likely to extend the duration of drought cycles and increase the intensity of wet cycles in parts of Southern California, including the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed.” With increase in climate change more evaporation in our reservoirs could happen and that means we should keep more of our water in the underground aquifers. In 2010 we had a tremendous amount of rain in California but a part of it had to be released into the ocean because we didn’t have the capacity to store it. Getting our aquifers cleaned and ready for storage along with dredging our reservoirs of silt would increase the capacity of water storage.

We, also, need to use imported water more wisely and consider reusing it before we send it out into the ocean. Some of that water that is in the San Fernando Basin is polluted but not all to the same degree. A lot of it can be cleaned up. Some will complain that cleaning up polluted water and pumping recycled water to groundwater aquifers uses large amounts of energy. The reply to the energy discussion is that just getting imported water to So. California is one of California’s biggest uses of energy. It is true that the water in the State Water Project travels north to south by gravity but then it hits the Tehachapis and it is pumped 2000 feet up a mountain to get it to So. California. This Northern California water, also, has to be pumped up hill by the Banks Pumping Plant at the Delta before it can start its 444 mile north-south gravity journey to So. California. That all takes a tremendous amount of energy. Regarding the water that comes from the east side of the Sierra, one of the 2 Los Angeles aqueducts also accomplishes water movement by gravity but the other one uses pumps. A quote from the River Project’s report, “Cleaning up groundwater can use half as much energy as importing water from the [Sacramento] Delta. Continued cleanup of the groundwater basins should be a priority In the future–85 percent of water supply for the City of Los Angeles is imported from distant sources via a delivery system that accounts for a significant percentage of our total statewide energy costs.”

Need to have the most water absorbent & sensitive areas as “no-build places”.

To take advantage of the wonderful resource of a highly absorbent aquifer we need to be able to use it when needed, so if there is a building placed on top of it then the aquifer can’t do its job. Cities need to make those places “no build” and only used for such activities as recreation. We can use public facilities like schools and parks to capture and store the water. (TRP)There are a total of thirty-six city and county parks within the lower Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed, which is the flat valley area, and seven adjacent parks, park space comprises less than 3 percent of the area. In the past parks have not been a high priority but if they can be seen as a way of capturing water they might be seen as more important and, therefore, receive more funding. Other public rights-of-way crossing the watershed include 27.75 miles of channelized streams and five transmission line corridors. These interconnect with spreading grounds throughout the watershed, providing an ideal opportunity to create green infrastructure for stormwater capture, groundwater recharge, and habitat that can provide a network of trails, pocket parks, and community gardens.” Prioritizing these areas for reclamation and restoration can have tremendous impact on our available amounts of local water supply. Along restored riparian (stream) corridors connecting the mountains and the washes, habitat for wildlife could be integrated with multiple-use parkland for people. Permanent protection of open space is warranted, particularly along these corridors and in the urban fringe above Hansen Dam.

City and county general plan policies should be revised to:

- avoid development along historic floodways,

- on hillsides,

- and in sensitive habitat areas;

- establish a long-term program to acquire land along floodways;

- protect existing parks, public rights of way, agricultural land, and surplus properties as open space;

- require provision of new, adequate open space as part of any concentrated redevelopment;

- improve and enhance public transportation;

- require on-site retention and infiltration of stormwater;

- and incentivize projects that balance recreation and habitat needs.

In the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed, nature balances our natural cycle of short periods of rain followed by longer periods of drought with the land’s ability to quickly absorb water where it falls and store it underground. But our land use practices have disconnected the land from the water, creating negative impacts to our water quality, and sending most of our precipitation to the ocean. We need a more integrated approach to meet future conditions.

Educating the residents & businesses in the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed

It is critical to continually educate watershed residents and other stakeholders about the special nature of the Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed and its significance as a sustainable habitat for plants, wildlife, and people and encourage their participation in habitat restoration projects. Ideally, K–12 schools in the watershed will permanently incorporate this plan’s watershed-specific grade-level curricula into their educational programs, and community colleges will encourage students to pursue site-specific watershed-based science that is relevant to them and to their community.

Reservoirs & Water Spreading Areas for Groundwater Recharge

(Map from The River Project)

(TRP) The four reservoirs in the Tujunga watershed (Lopez, Pacoima, Big Tujunga, and Hansen) have a total storage capacity of 39,517 acre-feet. (The reservoirs are in navy blue.) Snowmelt, and rainwater runoff stored in these reservoirs is slowly released and diverted into 5 spreading grounds (Lopez, Pacoima, and Branford spreading grounds along Pacoima Wash, and Hansen and Tujunga spreading grounds along Tujunga Wash. The spreading grounds are in orange and placed along the Pacoima & Tujunga Washes. These five spreading grounds collectively infiltrated to groundwater 32 percent of the local surface water conserved in all Los Angeles County between 2003 and 2006.

See a picture of a spreading ground below:

This is a spreading ground groundwater recharge basin (NPS for the River Project)