All the places where Los Angeles gets its water

All the places where Los Angeles gets its water

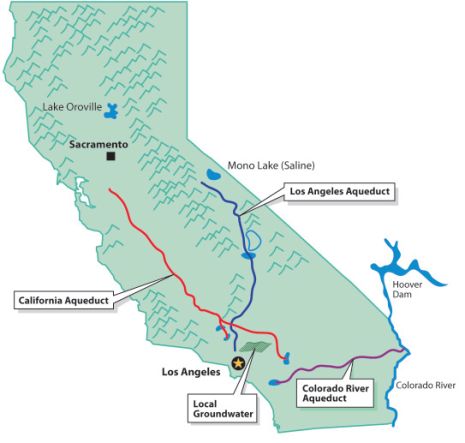

Los Angeles (L.A.) has many ways of getting water and there have been legal water wars started over how much water belongs to thirsty Los Angeles. You can observe the water routes on the above map. Per The River Project, “We currently spend $1 billion a year to import 85 percent of our water supply from other regions whose ecosystems are seriously threatened by that loss.” The water comes from the Colorado River and 2 places in Northern California, which are the Eastern Sierras’ Los Angeles Aqueducts & San Joaquin Valley route State Water Project. L.A. also gets some of its water from its underground aquifers. The largest one is in the San Fernando Valley but there are pollution issues with this aquifer. The first L.A. Aqueduct involves Mono Lake and the Owens River; the aqueduct goes from those places to LA. The history of how LA got that water isn’t very pretty. The LADWP is now reviving, with water, territories near the Eastern Sierra that were devastated by excessive LA water consumption. In California there are heated debates regarding how much water should go to saving our environment, especially the fish population, and what portions should go to farmers and cities. The Sacramento Delta estuary near San Francisco supplies two-thirds of CA’s water and it is at the heart of these debates. An estuary is a semi-enclosed coastal body of water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. As the fresh water flows into the estuary it acts as a barrier to keep the ocean’s salt water from mixing with the fresh water. When the river waters are decreased more salt water blends with the fresh water, which makes it less desirable.

First Los Angeles Aqueduct

William Mulholland is famously associated with the building of the first L.A. Aqueduct. Per Wikipedia, “The project began in 1908 with a budget of US$24.5 million. With 5,000 workers employed for its construction, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1913. The aqueduct consists of 223 mi of 12-foot diameter steel pipe, 120 mi of railroad track, two hydroelectric plants, 170 mi of power lines, 240 mi of telephone line, a cement plant, and 500 mi of roads. The aqueduct uses gravity alone to move water and also uses the water to generate electricity, so it is cost-efficient to operate. The construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct effectively eliminated the Owens Valley as a viable farming community, and devastated the Owens Lake ecosystem. Mulholland and his associates, including L.A. Times Harrison Gray Otis have been criticized for using deceptive tactics to obtain Bureau of Reclamation rights to the Owens River. Mullholland, his associates, and the City of Los Angeles forced farmers off of the land, using violent tactics to intimidate any farmers who refused to sell land to them. In response to these violent tactics, numerous Owens Valley residents sabotaged and destroyed portions of the aqueduct. The aqueduct’s water provided developers with the resources to quickly develop the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles through World War II. San Fernando Valley became part of Los Angeles to obtain these water rights. Mulholland’s role in the vision and completion of the aqueduct and the growth of Los Angeles into a large metropolis is recognized and well-documented. First Aqueduct ends at Upper Van Norman Lake near the I-5 in Granada Hills. There are problems with that area because of the Sunshine Canyon Waste Landfill locating in that area. There will be more on that issue further down in our “Garbage” section.”

Tufa towers in Mono Lake were exposed by water diversions

Cartoon by Willis Simms

Mono Lake

(Info. from Wikipedia) By the 1930s, the water requirements for Los Angeles continued to increase. LADWP started buying water rights in the Mono Basin (the next basin to the north of the Owens Valley). An extension to the aqueduct was built, which included such engineering feats as tunneling through the Mono Craters (an active volcanic field.) By 1941, the extension was finished, and water in various creeks was diverted into the aqueduct. To satisfy California water law, LADWP set up a fish hatchery near Mammoth Lake. The diverted creeks had previously fed Mono Lake, an inland body of water with no outlet. Mono Lake served as a vital ecosystem link, where gulls and migratory birds would nest. Because the creeks were diverted, the water level in Mono Lake started to fall, exposing tufa formations (see picture above). The water became more saline and alkaline, threatening the brine shrimp that lived in the lake, as well as the birds that nested on two islands in the lake. Falling water levels started making a land bridge to Negit Island, which allowed predators to feed on bird eggs for the first time.

In 1977 David Gaines & others from Stanford made a report on the ecosystem of Mono Lake that highlighted dangers caused by the water diversion. In 1978, the Mono Lake Committee was formed to protect Mono Lake. The Committee (and the National Audubon Society) sued LADWP in 1979, arguing that the diversions violated the public trust doctrine, which states that navigable bodies of water must be managed for the benefit of all people. The litigation reached the California Supreme Court by 1983, which ruled in favor of the Committee. Further litigation was initiated in 1984, which claimed that LADWP did not comply with the state fishery protection laws.

Eventually, all of the litigation was adjudicated in 1994, by the California State Water Resources Control Board. The SWRCB hearings lasted for 44 days and were conducted by Board Vice-Chair Marc Del Piero acting as the sole Hearing Officer. In that ruling (SWRCB Decision 1631), the SWRCB established significant public trust protection and eco-system restoration standards, and LADWP was required to release water into Mono Lake to raise the lake level 20 feet above the then-current level of 25 feet below the 1941 level. As of 2011, the water level in Mono Lake has risen 13 feet of the required 20 feet. Los Angeles made up for the lost water through state-funded conservation and recycling projects.

Second Los Angeles Aquaduct

Cartoon by Willis Simms

(Info. from Wikipedia) The second Los Angeles Aqueduct starts at the Haiwee Reservoir, just south of Owens Lake, running roughly parallel to the first aqueduct. Unlike the original, it does not operate solely via gravity and requires pumping to operate. It carries water 137 mi and merges with the original aqueduct near the Cascades, visibly located on the east side of the Golden State Freeway near the junction of State Route 14. (See a picture of the Cascades under the Garbage section.) Construction cost for the five year project that began in 1965 was US$89 million. In 1970, LADWP completed a second aqueduct. In 1972, the agency began to divert more surface water and pumped groundwater at the rate of several hundred thousand acre-feet a year. Owens Valley springs and seeps dried and disappeared, and groundwater-dependent vegetation began to die. In 1991, Inyo County and the city of Los Angeles signed the Inyo-Los Angeles Long Term Water Agreement, which required that groundwater pumping be managed to avoid significant impacts while providing a reliable water supply for Los Angeles, and in 1997, Inyo County, Los Angeles, the Owens Valley Committee, the Sierra Club, and other concerned parties signed a Memorandum of Understanding that specified terms by which the lower Owens River would be rewatered by June 2003 as partial mitigation for damage to the Owens Valley due to groundwater pumping. In spite of the terms of the Long Term Water Agreement, studies by the Inyo County Water Department have shown that impacts to the valley’s groundwater-dependent vegetation, such as alkali meadows, continue. Groundwater pumping continues at a higher rate than the rate at which water recharges the aquifer, resulting in a long-term trend of desertification in the Owens Valley.

The Amazing State Water Project The Metropolitan Water District (MWD) has tapped Los Angeles into the California State Water Project. (SWP). The SWP’s main stem starts from Orville Lake in far No. California to Lake Perris near Riverside in So. CA. It includes facilities that capture, store, and convey water to 29 water agencies. These facilities include: pumping and power plants; reservoirs, lakes, storage tanks; canals, tunnels, and pipelines. In some places they are not only providing water but delivering electricity at the same time. When water is needed, Lake Oroville releases water into the Feather River, which meets up with California’s largest waterway, the Sacramento River. The Sacramento River and 4 other rivers then flow into the Sacramento Delta. It is at the Delta where it is pumped by the Banks Pumping Plant into the 444-mile-long California Aqueduct. There are side aqueducts that pump water to water agencies along the way but the main stem flows down-hill through California just by gravity. This section of the California Aqueduct serves both the SWP and the federal Central Valley Project. The water flows through the central San Joaquin Valley farming region. The gravity flow stops at the Edmonston Pumping Plant, where the water is pumped 2000 ft. up over the Tehachapi Mountains to So. California. The west part of the SWP ends at Lake Castaic in the Angeles Forest and the Eastern Part ends at Lake Parris near Riverside in So. California. The SWP provides irrigation water to farms in the San Joaquin Valley, and is a major source of supply for cities in Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, and other parts of southern California. About 80% of California’s water is devoted to agriculture. There is considerable discussion regarding how much water should go towards farming, especially water-thirsty permanent crops like almond orchards.

The Sac. Delta’s Importance to California An article in the NY Times says that the Delta area “is so crucial because it provides two-thirds of the state’s water supply. Its massive pumping system routes water to cities and farmers alike, but the pumps have drained the delta region and become a kind of killing machine for endangered salmon and smelt. Add to those concerns the likelihood of increased salinity [to our fresh water] as sea levels rise due to climate change, diminished snow pack in the Sierra and the possibility of a major earthquake destroying the delta’s maze of 1,100 levees, and you get a perfect storm that could dwarf Hurricane Katrina as a natural disaster.” As was mentioned above, when the water gets to So. California it is pumped 2000 ft. up the Tehachapi Mountains to So. California and there are concerns regarding how that pumping system would survive a major earthquake. Because of possible earthquakes in the Delta and to the area near the Tehachapis, we need to rely more on our own local So. California fresh & recycled water supply. Now there is a plan to divert more water from the Delta; it is named the Bay-Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) and it is very controversial.

Water Supplies from the Colorado River Aqueduct to Los Angeles

The MWD, also, supplies some of the Colorado River water to L.A. through the 242 mile Colorado River Aqueduct. (Per Wikipedia, the system is composed of two reservoirs, five pumping stations, 63 mi of canals, 92 mi of tunnels, and 84 mi of buried conduit and siphons. Average annual throughput is 1,200,000 acre·ft. With the droughts in the west, the amount of water that Los Angeles is allowed could dwindle, so we need to provide local fresh & recycled water in its place.